7 Aug 2025 (Punjab Khabarnama Bureau)A growing trend of inward-looking trade policies across the globe is being increasingly linked to the unequal economic outcomes that followed the globalisation surge of the 1990s and 2000s, according to new economic assessments and policy analysis.

While the globalisation era ushered in unprecedented levels of cross-border trade, investment, and technological exchange, it also left behind a legacy of regional inequality, industrial decline in advanced economies, and widening wealth gaps—both within and between nations.

Winners and Losers of the Globalisation Boom

During the late 20th and early 21st centuries, global trade liberalisation policies—spearheaded by organisations like the World Trade Organization (WTO) and supported by major powers like the United States, European Union, and China—led to rapid economic integration. Large multinational corporations flourished, emerging economies like China and India witnessed double-digit growth, and global supply chains became deeply interconnected.

However, the benefits were uneven. In developed economies, many working-class communities—particularly in manufacturing hubs—experienced job losses as production shifted to lower-cost regions. At the same time, developing nations often remained confined to low-value segments of global value chains, limiting their economic transformation.

Economists now argue that the failure to address these imbalances has sown the seeds of today’s backlash.

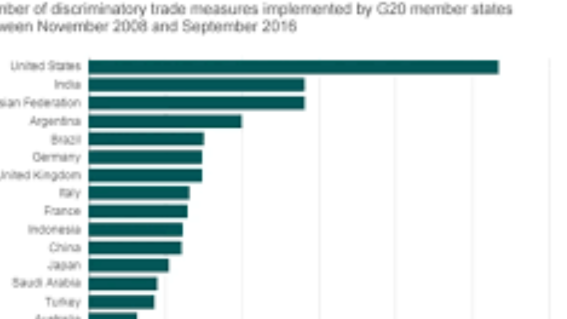

Rise of Economic Nationalism

In recent years, major economies have turned to protectionist policies, citing national security, self-reliance, and economic justice. The United States, under successive administrations, has implemented tariffs, reshored industries, and restricted technology exports. The European Union has proposed “economic security” frameworks aimed at reducing dependence on geopolitical rivals. Even India, a major emerging market, has shifted from its historic pro-globalisation stance to a model of “Atmanirbhar Bharat” (self-reliant India), focusing on domestic manufacturing and reduced import reliance.

“The return of protectionism is not surprising—it’s a political and economic reaction to decades of perceived neglect,” said Dr. Neha Kapoor, a global trade expert at the Centre for Economic Policy Research. “If globalisation had delivered more inclusive growth, the backlash might have been avoided.”

A Shift in Global Trade Norms

These shifts are altering the global trade landscape. The once-dominant rules-based multilateral system is increasingly being replaced by bilateral and regional agreements, industrial policy revival, and strategic trade controls.

The WTO has struggled to maintain relevance as disputes mount and countries increasingly bypass its dispute resolution mechanisms. Meanwhile, supply chain resilience, digital sovereignty, and critical technology control have become the new focus areas in trade strategy.

Looking Ahead

Experts warn that while some level of economic correction is necessary, excessive inwardness could harm innovation, slow global growth, and deepen geopolitical fragmentation.

“A balance must be struck between correcting past excesses and preserving the cooperative foundations of the global economy,” said Professor Marcello Li, senior advisor to the OECD.

Whether the world can reimagine a more equitable model of globalisation—one that safeguards national interests while promoting shared prosperity—remains a key question for the decade ahead.